|

|||||||||

| home | learn about your condition | about somatics | site contents | store | testimonials | about Lawrence Gold | get professional training | contact | |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

See also:

|

|

Unequal leg length generally indicates an injury to one side of the body (not necessarily a lower extremity injury) at some time in life, where the change of leg length came not from the injury, but from the protective cringing at the site of injury, leading to retraction of the extremity. Activity in stressful athletic situations (such as downhill walking or running) may further trigger the retraction response. |

|

||

|

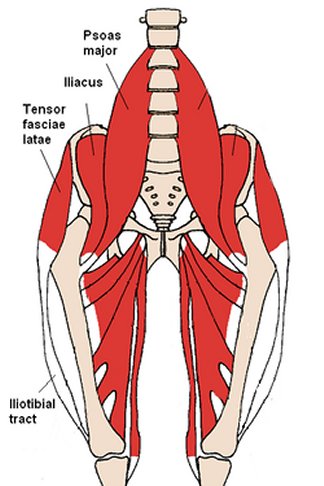

The tensor fascia lata (TFL) is a muscle that attaches the fascia lata (iliotibial band), a tendon of unusual shape -- a broad sheath that runs along the outer side of the thigh (like a cowboy's chaps) -- to the hip. It shares a movement with its neighboring muscle, the gluteus medius, which pulls the hip downward and extends the thigh backward. The gluteus medius has a different movement from the neighboring gluteus minimus, which flexes and internally rotates the thigh: the gluteus medius gets help from the gluteus maximus during the leg-back walking movement (when the thigh is externally rotated, right after foot-landing). Despite kinesiological analysis based upon its location, the TFL, in most movement, neither abducts nor flexes the thigh at the hip, but lifts the opposite side of the pelvis by pulling down on its attachment near the AIIS (anterior inferior iliac spine) during foot-down walking or running. That is, when weight is on one leg and stabilized by the ground, the tensor fascia lata contracts, pulls down on its own side of the pelvis and lifts the opposite side, as the opposite leg swings forward. The quadratus lumborum (QL) of the opposite side helps the lifting action of the TFL. In effect, the TFL and QL together cause a reaching or elongating movement of one leg by changing the side-tilt of the pelvis and pulling-in (retracting) the other leg. The abdominal obliques of the same side as the QL usually help. Knee-forward movement of the opposite leg in hip flexion occurs through the actions of the iliopsoas muscles and gluteus minimus. This synergy is better understood not as "muscles helping each other," but as "the brain coordinating movements," since coordination is a brain function and coordinated leg action is inherent in organisms with legs. For movement education purposes, a higher level of brain-integration results from movement training that involves both legs at the same time, each leg doing its respective, opposite, contra-lateral movements of walking, than of training that addresses one leg at a time. When someone gets injured in foot, leg, hip, pelvis, or even the ribs, the injury triggers these muscular responses in reaction to the pain, as movements to withdraw and so, to protect the injured place -- often as a long-term reaction that outlasts the time of tissue healing. The reaction produces the appearance of unequal leg length. Problems of apparent unequal leg length often involve a habitually contracted TFL on the longer-leg side and contracted psoas, quadratus lumborum ("QL") and (side waist muscles ) obliques on the shorter leg side. Hip joint compression may result, a problem that often leads to hip joint replacement surgery. Heightened tension of the TFL places strain on the fascia lata, inducing "I-T Band Syndrome," which can be relieved by freeing TFL and its synergists, generally through somatic education, which retrains muscular control. With this understanding, it is evident why movement training via somatic education is a superior approach to unequal leg length than massage, stretching, orthotics, icing, or cortisone injections, and how somatic education can complement and accelerate progress in physical therapy.

|

||||

|

The Institute for Somatic Study and Development

Herrada Road, Santa Fe, NM 87508

Lawrence Gold, C.H.S.E.

Telephone 505 819-0858 | PRIVACY POLICY | CONTACT: |