Somatic Education Exercises for Aging Exceptionally Wellby Lawrence Gold Certified Hanna somatic educator |

|

|||||||

Popular belief holds that the pains and stiffness of aging are inevitable and to be expected: that aging results from time passing. “You’re just getting older,” your doctor and your family say, and there the conversation usually stops. Popular belief holds that the pains and stiffness of aging are inevitable and to be expected: that aging results from time passing. “You’re just getting older,” your doctor and your family say, and there the conversation usually stops.

The thinking is that your parts are wearing out, and that they’re supposed to. It’s how people think of the human body — as a “marvelous machine.” Don’t buy it. There’s more to it than the passage of time and the human body is more than a marvelous machine. You are more than a marvelous machine, aren’t you? While certain aspects of aging are linked to our genetic destiny, other changes have nothing to do with our genetic destiny, but with how injuries and stress leave their marks upon us as changes of movement-memory, of muscular tension, and of posture. Those changes are, in most cases, within our power to to reverse, normalize, and improve to superior levels. Is there a hidden and larger significance to the observation that active people age better than relatively inactive people? There is. (It goes along with the saying, “Retirement is the waiting room for death.”) There exists a seemingly innocent condition that underlies much of the pain and stiffness attributed to aging: accumulated muscular tension. Accumulated muscular tension underlies the joint compression and breakdown diagnosed as osteoarthritis. Accumulated muscular tension often goes unnoticed because it builds so gradually that we get used to it, because we don’t recognize the significance of poor posture, and because medical practitioners are not trained to recognize its larger significance — other than at the sites of pain or grossly restricted movement. Desensitized as we are to our own condition, muscular tension accumulates and so do the consequences: being off balance and prone to falls, feeling tired all the time, depressed mood, and the appearance of chronic ailments. Accumulated muscular tension is a drain, an inconvenience, a degradation of life, and ultimately, a hazard. By dispelling accumulated muscular tension and preventing tension from accumulating, you can prevent your joints from degenerating, improve your movement and balance, and feel more energetic; you can reclaim much of your flexibility. You can forego the cane, get off the walker, or avoid the wheelchair. It takes more than massage. It takes self-grooming of a particular kind — the kind that removes the lingering effects of injuries (the limp), purges the stresses of life (the stoop or bad back), and liberates you from the ten thousand shocks flesh is heir to (pain). This entry talks exactly about that form of self-grooming (it’s not strengthening, stretching, or cardiovascular exercise, not diet — but something rather more direct and immediately effective). Because it’s new, you’ll learn something, here. THE OBVIOUS SIGN OF APPROACHING DECREPITUDEHere’s a leading question: How can you tell an “aged” person at a distance? It’s by their posture and movement, isn’t it? Our posture goes into our habitual way of moving. Much has been attributed to osteoporosis and osteopenia — loss of bone density — as causing changes of posture. While true to some degree, it’s largely a “red herring”; muscular tensions cause much more postural change than does osteoporosis. Muscle tension shapes our posture, limits our flexibility, and affects our comfort. The posture of aging reveals accumulated muscular tensions that you may have carried for years, largely without knowing it.Does this seem all too obvious? Then why don’t most people do something about it? Why do so many people resign themselves to the cane, the walker, the wheelchair? Maybe, it’s because the usual methods of muscular conditioning and therapy don’t work very well; maybe it’s because people get so tight and stay so tight that their joints break down. Have yours? SOURCES OF PAIN AND STIFFNESSWhen muscles get tight and stay tight, they cease to be elastic; they restrict movement. That sense of restriction is what people confuse with stiff joints and call “stiff muscles”. (Muscles can’t get stiff; they can only tense or relax.)Muscles held tight for more than a few seconds get sore and prone to spasm (cramp) — the proverbial “burn” of exercise that athletic trainers say to go for. It’s muscle fatigue, nothing more glamorous than that. It’s the product of tight muscles, an unhealthy sign, when it persists. Muscles held tight days, weeks, and years compress the joints they pass across; joint pain, breakdown, inflammation and dissolution follow. The name for cartilage breakdown and inflammation is, arthritis (literally translated from Latin: “inflammation of a joint”). Even if there were a genetic origin to arthritis, it would be in addition to this compression process, which causes joint breakdown all by itself. The combination of muscle fatigue (soreness) and joint compression create much of the chronic pain and stiffness of aging. “Sore to the Touch”Most people are sore to the touch in one place or another — not because they are “old”, but because they are tight, and their muscles, fatigued.The problem exists, however, not in the muscles themselves, but in the brain that controls them. The problem is one of “muscle/movement memory”, which controls movement, tension level, and posture. The reason why skeletal adjustments, massage and stretching so often provide only temporary relief is that muscle/movement memory runs the show. You may temporarily force muscles to relax with massage or a quick stretch, but of muscle/movement memory is set to a high tension level, we get tense, again, in short order — whether hours or days. Forming Tension HabitsPeople go through a lifetime doing either one of two things: tensing or relaxing.Think back to a time in your life when you were in a stressful situation — one that you knew might last a while or that lasted longer than you expected. Notice how you feel when thinking about it. Do you tense or relax, thinking about it? How were you, then? Did you manage your tension or ignore it? Did you turn your attention to “more important things”? Did you get used to your tension? If so, you probably lost some of your ability to relax (in the muscular sense, as well as the emotional sense). Over your lifetime, did you get more flexible, or more stiff? Sudden onset of stiffness or an episode of pain is how you know it’s muscle/movement memory. Joints don’t change that quickly. Another way tension habits form is through physical injury. It’s not the injury, but the reaction to it, that triggers tension habits. When we get hurt, we guard the injured part by cringing — pulling out of action. Many injuries make such an impression upon us that we continue the cringe for decades, automatically and without awareness. We may not notice low-level cringing, but as tension accumulates, a low-level cringe often becomes a high-level of contraction that at last surfaces as a mysterious episode of pain — the cause having occurred years ago. Even physical fitness programs can lead to chronic tension. Many kinds of fitness training emphasize strength and firming (tightening) up. Rarely do they teach a person to relax. More often, they teach a person to stretch and “warm up”, which is not the same as teaching relaxation. So many fitness programs (or at least the way some people do them) cause them to form tension habits. Thus form tension habits that lead to chronic pain, stiffness, inflammation and joint damage. Even without arthritis, accumulated tension adds drag to movement. The combination of drag and pain drains us and makes us feel tired all the time, “old”. It’s not age; it’s pain and fatigue. Seem familiar? So, it’s not so much our years as the tension that accumulates over the years that causes the pain and stiffness of aging and the loss of the agility of youth. BACK TO EASIER MOVEMENTThe pain and stiffness of aging start out as temporary tensions that become learned habits. Those habits can be unlearned, pain dispelled, comfort restored, stiffness softened, mobility improved. The odd thing is that our tension often seems to be “happening to us” — rather than something we are doing. Much of it exists below our “threshold of consciousness”. We’re “used to it”; we don’t notice it. “Somatic education exercises” effectively soften the grip of tension — not merely temporarily, but cumulatively, progressively, durably. The word, “somatic”, refers to your sense of yourself, as you are to yourself. It means “self-sensing, self-activating and self-relaxing” — the way you sense and control chewing. Somatic education exercises are an entirely different class of exercises from strengthening exercises or stretching exercises (whether athletic stretches or yoga). They have a quality to them akin to yawning. By instilling healthier patterns of muscle/movement memory, they improve posture, flexibility, and coordination. Tension eases and pains disappear. They make movement without pain possible, again. Healthy aging is more likely if you eliminate the causes of aging you can control. Age management involves more than drugs for blood pressure, crossword puzzles for your brain, cardiovascular exercise for your heart, weed which you can buy weed online in Canada if you live there, or stretches for your muscles; it involves grooming yourself of the accumulated effects of injuries and stress — not merely psychologically, but physically. A healthy diet, a rich social life, and pursuing our interests are important aspects of successful aging. So are somatic education exercises — without which, you now know the probable consequences.

|

||||||||

Regrow Cartilage

QUESTION from a reader who asks how to regrow/repair cartilage:

“Hi Lawrence. Do you have any information of how to 1) repair or regrow cartilage in the joints, hips specifically, and 2) how to eliminate bone spurs? I’m having great progress with somatics to improve posture and reduce tension and muscle pain, but I still get a sense of a deeper soreness and also grinding in the joint which feels like it could be from the cartilage wear and spurring that was detected in my joints. Any advice on this? Is it indeed possible? 😉 Thanks!”

ANSWER:

To regrow cartilage, you need some cartilage in the joint; the remaining cartilage is the “seed” for regrowth. Then, you need to remove overcompression by freeing the surrounding musculature

If there’s no cartilage left, I don’t know.

Sometimes, muscular soreness near a joint is mistaken as joint pain. In that case, there’s no need to regrow cartilage.

For hip joints, the muscles involved are the gluteals (see The Cat Stretch Exercises, with a modification of Lessons 1 and 5 for the gluteus medius muscles) and Lesson 3, the adductors, hip joint flexors and psoas muscles (Free Your Psoas), and the deep adductors (obturators)(The Magic of Somatics).

With the pressure removed, cartilage can regrow (slowly). I don’t know the value of chondroitin sulphate for growing cartilage, except that when muscular tension around the joint is high, it’s impossible to regrow cartilage.

As to bone spurs (osteophytes), same thing. Bone spurs grow along the line of pull of chronically tight muscles, at their tendonous attachments.

So, bone spurs and cartilage loss come from the same cause: muscles held tight over a long period. Bone spurs can dissolve, and cartilage can regrow, when the cause is removed.

Please also see, “Completing Your Recovery from an Injury”.

in your service,

Lawrence Gold

SuperSize That Somatic Exercise — The Diamond Penetration Technique | SuperPandiculation

The Diamond Penetration Technique is a way to get more done with less effort and less time, and more brainpower, in clinical sessions of Hanna somatic education(R) or with somatic exercises. The maneuver enhances or potentizes pandiculation (“Whole Body yawn”) technique.

There’s a lot, here, so as you learn this technique for “supersizing” somatic exercises, learn one step at a time before adding the next. “Learn” means “learn”, not “do once and then move one.” Really. Be merciful to yourself and take bite-size pieces, only.

In his original instruction to us, his students of his 1990 Clinical Somatic Education training, Thomas Hanna showed us how to use The Pandicular Response to free people from the grip of The Landau Reaction, which tightens the back/posterior side of the body and, when excessively activated for long periods of time, causes back pain, sciatica, tight shoulders and tension headaches.

In Lesson One (Green Light lesson) for Landau Reaction, he showed us how to coach our client through a Whole-body yawn (pandicular maneuver), beginning with a lifting action of one leg and its opposite shoulder, arm and hand, and head, as in the video, below — to lower them by stages in steps of relaxation, with a mini-in-breath with each mini-lift . . . . . before lowering some more.

First, the video, so you know for sure the maneuver to which I refer.

17 Minute First Aid for Back Pain

I have found that “staged” or “stepped” relaxation can be made more powerful by a technique that I have named, “The Diamond Penetration” maneuver. The reason I have named it The Diamond Penetration maneuver will become clear to you once you start doing it. For now, I say that it makes use of The Power of Recognition, as I have described it in the linked article, “Attention is a Catalyst“, to amplify the effectiveness of pandiculation, or any other therapeutic or educational technique, for that matter. Assisted Pandiculation is accelerated learning, and learning involves recognition and development, based upon memory. Memory, learning, recognition, function and development are five development stages of a single function. There’s one more.

Memory — the ground function, memory — persistence of pattern, memory

Learning — modification of the ground function into a durable pattern of memory

Recognition — the closely approximate match of some memory with an experience happening now

Function — initiation of action, memory activated and applied to this moment

Integration — facility to move freely and functionally among different remembered patterns

Evolution — expansion of attention beyond both memory and the moment — the space of emergence of newness, for patterns newly emerging into the moment, to be remembered into existence.

Take the starting initials of each, and you get MLRFIE! Well, that’s as far as we’ll go with that one, folks — at least for now. We’ll come back to that strange, unpronounceable acronym, later.

In his demonstrations to us, Thomas Hanna had the person on the table lower the leg part way, then lift a bit, then lower some more, repeating by stages, to complete rest. He even commented that that same maneuver was what Joe Montana did, spontaneously, after his back surgery and commented ruefully about to what the rapid improvement was attributed — namely, surgery and physical therapy!

Here’s the “inside” of that maneuver: The lifting action produces a sensation. By re-lifting after lowering part way, the client re-locates the sensation of lifting (contracting the muscles of lifting the leg). To re-locate the sensation activates the power of recognition, which is central to all learning. (No recognition — no learning.)

That’s the central principle of The Diamond Penetration Technique.

Here are the advantages of using The Diamond Penetration Technique. It:

- rapidly penetrates Sensory-Motor Amnesia

- rapidly awakens sensory awareness and motor control that has never been awake, before (penetrates Sensory-Motor Obliviousness)

- speeds integration of multiple “movement elements” into a single coordinated action

- increases the result of a single pandiculation — relaxation and control

- decreases the number of repetitions needed for pandiculation to get the desired result

- shortens the time needed to get a good result from a somatic exercise lesson

Obviously, these benefits are interrelated and just a tiny bit useful when working to transform yourself.

I have elaborated that principle into a very powerful technique that merits the name, “Diamond Penetration”. Very powerful. Clinical practitioners can apply this technique to assisted pandiculation maneuvers; clients can apply it to somatic exercises, and to free-form pandiculations you may do when working out pains or restrictions for which no somatic exercise currently exists.

I have developed several increasingly powerful variations of The Diamond Penetration Technique, which I outline, here.

- “The Quick Return”

- “The Quick Return and Sustained Hold”

- “The Two-Movement-Element Combination”

- “Twos and Threes”

- “The Diamond Pattern”

- “The Multi-Movement-Element Combination Sequence”

As you can see, these variations increase in complexity. The way to learn them is to do and learn them one-at-a-time, not to try to understand them by reading or to memorize them all before doing them.

Now the instruction. I’m going to spread things out in detail, so stay with me.

The Quick Return

Repetition is basic to recognition.

In The Quick Return, we contract into movement and feel the sensation of the end-point of movement (“where we end up in the movement”), then relax part-way for an instant, then re-contract and re-locate the exact same sensation.

- Contract and feel what’s tight.

- Relax part-way.

- Re-contract to feel the exact same thing.

That’s a Quick Return. It activates The Power of Recognition (familiarity). We might call each repetition “a pulse of sensation.”

An example from Lesson One could be,

“Lie on your belly, head turned, with your thumb in front of your nose, your hand flat on the surface. Lift your elbow to the limit. Feel what that feels like in your neck and shoulder.

Now lower it a bit, and immediately lift again. Find the exact same sensation at the same place. That’s called, ‘a Quick Return’. Remember that for use, as we go along.”

“Mini Quick Returns”

During the relaxation phase of pandiculation, you can do “mini” Quick Returns on the way to complete relaxation.

PRINCIPLE

It takes two incidents or occasions to activate memory; prior to that, it’s just sensory awareness or cognition — no recognition. In fact, without recognition, something happening is identical to nothing happening; we don’t know what it is, other than that it’s “something but we don’t really know what”, which makes the experience somewhat evanescent.

Now, the thing that makes one occurrence different from two occurrences of the same thing is the contrast between “happening” and “not happening”. “Not happening” has to separate the two occurrences. That’s the principle, “Somas perceive by contrast,” or “Somas can perceive only changes.” In somatic education practice, the common contrast is between activity and rest — which is why I instruct clients, “Come to complete rest between repetitions.” Without “not happening”, there’s only one long incident.

The Quick Return and Sustained Hold

We know that for a sensation to emerge, and for attention to steady on a sensation, takes time. Quick things escape our noticing.

So, after the Quick Return, we sustain the action (“sustained hold”) to let it “fade into view”. Attention steadies in and on the sensation. The sensation becomes more vivid.

To apply a sustained hold, you do a series of Quick Returns (however many) then hold the final Quick Return; during that holding time, remember the pattern and timing of the Quick Returns that got you there, i.e., brought you into this holding pattern. Then, you slowly relax, taking time at least equal in length to the memory . . . . . or longer . . . . to complete relaxation.

Thus, you

- first sense and do the movement, and hold, then

- remember the movement while holding its pattern, then

- back out (ease out) of the movement slowly and deliberately to complete rest.

You come to know the beginning of the movement, its middle, and its end — initiating it, sustaining it, and letting it go.

How useful do you think that might be for learning to occur?

The instruction would be:

“Do a Quick Return and hold. Now, slowly relax.”

PRINCIPLE

Experience takes time.

Sustain the hold for the total amount of time it took to do all the Quick Returns. For two Quick Returns (three movements into position), sustain the hold for a “count” of three — equal to the time it took to contract and then do two Quick Returns — then relax during a count of three. (That doesn’t mean, “Relax and then count to three.” It means, “Take a count of three to go from contracted to relaxed.”)

Comparing Memory to Action

Integrating the flesh-body and the subtle-body (mind).

Having done a Quick Return and Hold, you now remember the sensation of movement and then do the movement, again, to compare it to the memory. Are they the same?

You might then repeat the movement and compare to memory until the movement and the memory closely match.

PRINCIPLE

Memory is the root of action.

The Two-Movement-Element Combination

Coordination develops when we combine two actions (“movement elements”) into one.

In the Green Light lesson, we lift the elbow-hand-head-shoulder with the opposite-side leg, as in the video. Those are the two movement elements.

Using the Quick Return, the instruction could be:

- “With your hand flat on the surface, lift your elbow to the limit. Now do a Quick Return (relaxes and re-contracts) and hold.

- Now, lift your straight leg. Now lower it a bit, and do a Quick Return.

- Now, do a Quick Return of both, together.” (combination Quick Return)

When doing the Quick Return of both, together, the movements should be synchronized to start and end together. That develops coordination (integration).

HIGHER INTEGRATION

I have discovered another kind of “three” that rapidly integrates two movement elements. It goes beyond The Equalization Technique.

It goes like this.

Do a Quick Return of the first movement element and hold.

Do a Quick Return of the second movement element and hold.

Both movement elements are now active. Now, integrate them with each other in a three-part maneuver:

Pulse the first movement element to firm up the second movement element.

You’ll feel it. If you don’t feel it, you’ve partially lost the second movement element. Bring it back and pulse the first movement element, again, until you feel it make the second movement element stronger.

Pulse the second movement element to firm up the first movement element.

Pulse the first movement element to firm up the second movement element.

You’ve now forged a better connection between the two movement elements. That’s the other kind of “three” maneuver, an integration maneuver.

You can use this “three” maneuver with any two synergistic movements of any somatic exercise (“synergistic” means that the two movements help each other).

Twos and Threes

Now, we get a bit more sophisticated.

Once you or a client have done a combination Quick Return, you’re in a position to do two Quick Returns. That makes for, not two quick experiences of the same thing, but three.

If that’s confusing, lie on your belly with your thumb by your nose and do two Quick Returns. You’ll see it creates the same sensation three times. Just do it.

Here’s the thing: If, with a single movement, you alternate between one Quick Return (to complete relaxation) and two Quick Returns, you alternate creating two experiences of a sensation with creating three experiences. That’s a contrast, in itself.

When done as a combination Quick Return, it’s a very powerful way of creating learning that I have found causes a series of internal shifts of sensory-motor organization.

The instruction could be:

- Lift your elbow. Now do a Quick Return and hold.

- Lift your leg. Now do a Quick Return and hold.

(two movements at the same time) - Now, do two combination Quick Returns (a “three”). Relax completely.

- Now, do one combination Quick Return (a “two”). Relax completely.

- Alternate doing two and doing one. Continue until you get better coordinated.

PRINCIPLE

Changes of patterns awaken the Power of Recognition and trigger learning.

The Diamond Pattern

Here’s a “diamond” pattern (number of repetitions:

1 2 3 4 3 2 1

.

. .

. . .

. . . .

. . .

. .

.

The instruction could be:

- Do (some action, such as lifting the elbow) and hold. Now, relax completely.

- Do one Quick Return (2 experiences of a sensation) and hold. Now, relax completely.

- Now, do two Quick Returns (3 experiences of a sensation) and hold. Now, relax completely.

- Now, do three Quick Returns (4 experiences of a sensation) and hold. Now, relax completely.

- Now, do two Quick Returns (3 experiences of a sensation) and hold. Now, relax completely.

- Now, do one Quick Return (2 experiences of the sensation) and hold. Now, relax completely.

- Now, do the action without a Quick Return (1 experience of the sensation). Hold before relaxing to complete rest.

The experience “backs a person out of contraction” and gets them able to feel more and more with less and less stimulation.

To see the value, try it with any movement or combination.

PRINCIPLE

Bucky Fuller pointed out that four incidents or occasions of an event were the minimum needed to recognize a stable pattern.

It goes like this:

- one incident or occasion:

internal experience: “Something has happened.”|

(capture of attention) - two incidents or occasions of the same thing:

internal experience: “This seems familiar.”

(recognition) - three incidents or occasions of the same thing:

internal experience: “There seems to be consistency.”

(building upon recognition – “There is something to learn, here”) - four or more incidents or occasions of the same thing:

internal experience: “There’s a consistent pattern, here.”

(development of knowledge)

Test this out in yourself by using your imagination.

APPLICATION

The Diamond Penetration Technique can be applied to single movements, to simpler somatic exercise lessons (e.g., those of “The Cat Stretch” or “The New Seated Refreshment Exercises”), to more complex somatic exercises that involve as many as seven movement elements in combination (e.g., “Free Yourself from Back Pain” or “The Five-Pointed Star”), or to inherent action patterns such as those of walking (“SuperWalking”), twisting, or wriggling.

This technique lends itself to The Equalization Technique, discussed in The Evolution of Clinical Somatic Education Techniques. In a combination Quick Return, match (by feel) the effort of one movement to the effort of the others; equalize them. Read the article.

The Multi-Movement-Element Combination Sequence

In general, it goes like this:

- Do a Quick Return of the first movement element, and hold.

- Do a Quick Return of the second movement element, and hold.

- Do two combination Quick Returns of the two movement elements, and hold.

- Do a Quick Return of the third movement element.

- Do two combination Quick Returns of the three movement elements (with Equalization Technique).

- Do a Quick Return of the fourth movement element (if there is one).

- Do two combination Quick Returns of the four movement elements (with Equalization Technique).

Keep adding movement elements that fit together (synergistically) until they are all assembled into one Grand Coordinated Movement.

You can do Mini-Quick-Returns with the entire movement pattern, through the relaxation phase to complete rest.

Matching Memory (Subtle Body) to Sensation (Dense Physical Body)

Having done any of the variations, above, you can end a sequence by alternating a single quick return with a moment of rest (or a moment of holding the contraction), during which you remember (or imagine) and compare what you just felt with what you remembered.

You alternate a single quick return with remembering/imagining until your memory matches the experience very closely.

Then, you do a final contraction, hold and remember, then relax very, very slowly.

When the memory matches the experience, you have integrated your subtle and dense physical bodies. Relaxing at that point enables you to come out of contraction much more completely than otherwise.

PRINCIPLE

We perceive by means of contrast; we correct things by making a comparison. We gain control by means of memory.

SUMMARY

The essence of this technique involves repetitive pulsing of movements, activation of memory, matching the sensation you remember with the sensation you experience as you do the movements, and slow, controlled release of muscular efforts.

- Each pulse of movement creates a sensation that you locate as your “target” for Quick Return.

- In each repetition of a pulse, you locate the identical sensation in the identical location.

- In combination Quick Returns, you locate the identical feeling of the whole movement each time you do the combination movement.

- Each pattern of repetitions (2’s, 3’s, “diamond pattern”) magnifies the Power of Recognition.

Now you know what MRLFIE stands for!

I know there’s a lot. That’s why you start simply, at the beginning. Internalize (learn) each level of complexity until you have it all under your belt.

If you’re a practitioner, teach your clients to their capacity, but not beyond. If they lost the pattern, have them go back and coach them until they’ve mastered what you’ve covered, before going further.

COPYRIGHT 2011 Lawrence Gold ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

reproduction by permission, only

Somatic Education | Intrinsic Action, Extrinsic Action and “The Controlling Moment”

a deeper view

of somatic education

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” So wrote Benjamin Franklin in Poor Richard’s Almanac.

Failing that, another saying carries the point: “The biggest problem could have been solved when it was small.” So wrote Lao Tzu, a Chinese Taoist sage, in The Tao Teh Ching, an ancient text of wisdom.

Changing behaviors and entrenched conditions isn’t as simple as it sounds — a mere decision powered (at best) by enthusiasm — as anyone who has worked to change a habit has found.

People do it by “trying” — working harder to change — rather than by uncovering their/our own remaining impulse to be “the old way” — working smarter.

However, without taking into account the root of action, any change of action remains incomplete and in conflict with old ways of acting. This understanding applies as much to social politics as it does to individual behavior and experience. That’s why, “You can’t change minds with guns.”

There’s a way of “working smarter”, rather than harder — and that is part of what I cover in this entry.

There’s a “Root” of Action??

The idea that there is a root of action doesn’t occur to most people. That’s because people generally experience action — theirs and others — only once it is well underway. The root of action, because it is small, subtle, goes unnoticed.

So, I will, in this entry, illuminate the nature of the root of action (and it isn’t psychological, but more primordial/rudimentary than that).

In the process, I will show the relationship between the subjective experience of the root of change and the objective (and outwardly observable) bodily sign of the root of action.

Let’s get started.

The Root of Action

The root of action is so common as to go unnoticed, except in certain specialized situations. Its word is, “readiness”.

Readiness is not merely an emotional state, a state of anticipation. (“Yeah, boss! Yeah, boss!”) It’s a state of preparation, the first step of shifting from rest (unreadiness) into action. (“On your mark, get set . . . “) It’s a “steering” action, the step of organizing oneself for a particular activity, generally based upon the memory of the action we are about to do, but also modulated by the relationships of the moment. It’s that subtle.

Because it is that subtle, as subtle as memory and the subtle effects of one person or place upon another, it generally goes unnoticed.

Memory and imagination go together, are two sides of the same coin.

The act of getting ready is preparation for a leap into a (however vaguely imagined) future which has some connection with a memory.

I call the moment of getting ready, “The Controlling Moment.” As we leap (or subtly, imperceptibly drift) into action, we rally our determination, springing (or gliding) forward from that controlling moment into full action.

As we launch into action, we power up. The controlling moment points our direction. Powering up builds upon the controlling moment, and away we go.

Now, here’s the odd thing about human beings: it’s common for us automatically to redirect our launch, so that what we do after the Controlling Moment misses the mark we (think we have) set in our Controlling Moment.

The act of redirecting ourselves occurs automatically, involuntarily, and is based upon memories of life situations similar to the one into which we are launching. Fears, conditioning, beliefs all change our trajectory, but “behind the scenes”, without conscious awareness. That means we get unanticipated results.

Not only do they change our trajectory; they also disguise or obscure the Controlling Moment of that action, so that an observer of our action often can’t tell what our precise intention was at the controlling moment — and we, ourselves, find it difficult to tell why things went awry. (“The road to Hell is paved with good intentions,” a pathetic saying based on the presently-described dynamic) What we and others perceive is everything that followed the Controlling Moment of that action, but the Controlling Moment remains obscured and obscure.

Why? Because the experience of “powering up” is so much “louder” than that of The Controlling Moment. The root remains buried.

That’s why it’s so difficult to self-correct, to change habits, and to understand the motivations of others whose actions we observe.

Two “Layers” of Action

We may regard The Controlling Moment as the core of an action (steering) and Powering Up as the extension of that core (acceleration).

Another odd thing, however: the two layers don’t always go together. Sometimes, we get ready for an action but refrain from carrying it out; sometimes, we do an action for which we are not really ready, and our heart really isn’t in it, but carry it out, anyway. We counteract our own Controlling Moment or we act without the precise internal guidance of a mature Controlling Moment.

In those cases, we have a condition of self-arrest (Controlling Moment without Powering Up — ineffectuality) or poorly organized action (undeveloped Controlling Moment and lots of Powering Up — stupidity or clumsiness).

In such cases, a residue of the action (or lack of action) remains in memory. The residue of self-arrest is regret, frustration and/or self-recrimination; the residue of poorly organized action remains in memory as a sense of guilt, shame, and/or lower self-esteem.

Integrity

What’s lacking when we have one but not the other is integrity.

Integrity is intelligent, well-regulated, well-modulated power.

In other words, when we have one but not the other, we fail either to exercise our intelligence adequately or we fail to exercise our power appropriately.

What happens as aftermath when we act without intelligence or without well-regulated power is we experience our lack of integrity as disempowerment.

What to do? What to do?

Forging Integrity

Congruence between our Controlling Moment and our Powering Up shows up as integrity. To forge integrity, we must correct one or both of our errors — the error of acting without adequate intelligence or an error of the exercise of power .

However, it’s not sufficient merely to power up; we must power up to a degree of intensity appropriate to our circumstances. Likewise, it’s not sufficient merely to power up to an appropriate degree of intensity; we must power up intelligently, which means in alignment with the intention present in our Controlling Moment. The Controlling Moment is the truth of any action.

The kicker is that we can’t have intelligence about a Controlling Moment buried by an unintelligent powering up — and powering up always buries the Controlling Moment simply because it’s louder.

So, we have to uncover the Controlling Moment underlying any action or habit we find problematic.

How do we do that?

The First Moment of Attention

Self-correction requires that we catch the fault when it is small. Otherwise, we have to deal with both the momentum of an action in progress and the direction of that momentum. Think of turning a vehicle at slow speed vs. at high speed.

Again, unfortunately, we may (and commonly do) miss the Controlling Moment.

One way to catch the Controlling Moment is to slow down so that we can observe the first moment of action, the Controlling Moment.

Another way to catch the Controlling Moment is to repeat the action with close attention each time, so that we ultimately catch the Controlling Moment.

And yet another way to catch the Controlling Moment is to alternate doing an action with refraining from that action, so that, by virtue of the contrast between doing and not-doing, we get enhanced perception of the action.

And yet another way to catch the Controlling Moment is to take instruction (and example) from someone adept at the intended action, so that, by virtue of the contrast between their competence and our incompetence, we catch our own errant Controlling Moment and correct it, with repetition, by degrees (successively accurate approximations).

But, whatever the approach, we must catch the Controlling Moment, so that we perceive the contrast (or difference) between our Controlling Moment and the subsequent Powering Up (which may be out of close alignment with our Controlling Moment) — so that we can self-correct at the root of action.

A master of anything is one who has done so.

I’ve just outlined the theoretical (not hypothetical) underpinning of action and of change of action, and also of somatic education as a way to upgrade our way of operating in life. I’m going to leave you with that basic understanding without outlining specific techniques of somatic education so that you can form the intention and your own Controlling Moment to improve your access and control of your own controlling moments. It’s known as “sharpening the tool”.

What follows is an addendum of interest to practitioners of somatic education and Rolfers. To continue this consideration, please see this entry on The Big Pandiculation.

We continue.

For Practitioners of Somatic Education

Feldenkrais pointed out, in “Body and Mature Behavior”, that laboratory studies showed that we can sense a stimulus about 1/20th of the intensity of another, immediately preceding stimulus. That means, when a stronger stimulus immediately precedes another, weaker, stimulus as little 1/20th as intense, we can sense both, but if the weaker stimulus is less than 1/20th as intense, we may not be able to sense it.

Thomas Hanna, developer of Hanna somatic education, pointed out that to effectively alter a pattern of function, we must recover awareness and control of that pattern of function by deliberately cause it at a level of intensity at least equal to that of the same pattern, when caused by involuntary habit. By matching or exceeding the level of voluntary intensity to the intensity of the involuntary habit, control shifts from involuntary habit to voluntary performance. At that point, change is possible.

However, to make a change, we must reach, or catch, the Controlling Moment, and that requires two things: that we:

- closely match the voluntary pattern of action to the habitual/involuntary pattern.

- maintain continuous sensory awareness from full intensity if the action all the way to zero intensity.

In practice, 1. requires that we compare (by feeling) our voluntary action to the habitual action and self-correct until they closely match.

In practice, 2. requires that we either go slowly enough that neighboring (or successive) “takes” of sensory perception are less than 20:1 (“takes” of sensory perception can’t be continuous due to the way our nervous systems function, in which our brains link successive “snapshots” of perception the way movie films and TV images present successive “shapshots” of movement that our brains link together — via memory — into the impression of continuous action). Since, by tendency, we lack continuous perception of habitual actions, we may need to make numerous repetitions of the action to develop sufficient perception to apprehend the Controlling Moment and to make the change.

For Rolfers

Rolfing, as commonly practiced, is a soft-tissue manipulation process that, as Ida Rolf put it, is an educational practice intended to evolve more efficiently functioning human beings. As such, it is a form of somatic education, although indirectly so (except for its more direct, but less potent form, “Rolfing Movement-Integration”.

Ida Rolf made a distinction between “Intrinsic Movement” and “Extrinsic Movement.” She defined “extrinsic movement” as “immature movement” and “intrinsic movement” as “mature movement.”

Now to clarify those meanings.

Intrinsic Movement is movement we originate with awareness of the Controlling Moment — the root of action — intention.

Extrinsic Movement is movement we originate with more concern for how the movement looks or conforms to the expectations of others (or social standards) than by how it feels — and so is immature movement that we may characterized as “obedience”, “conformity”, “going through the motions”.

She also distinguished two “layers of depth” of the musculature and myofascial web: intrinsic musculature and extrinsic musculature, or “core” (intrinsic”) and “sleeve” (extrinsic).

The intrinsic muscles are those most immediately responsive to the shift from rest into full activity, which corresponds to the shift from rest (or unreadiness) into readiness for activity. Examples of intrinsic muscles include the finest, deepest muscles of the spine, the tongue, the muscles of focusing, the psoas muscles.

The extrinsic muscles add power to the pattern of organization set by activation of intrinsic muscles. So, it may be said that visually seeing organizes the body for motion. Thus, “Look where you’re going,” has an intuitively understandable meaning.

Another distinction she made was of two variations of poor integration:

- soft (open or free) core, hard (restrictive or tight) sleeve — conformity — “going through the motions,” “going along to get along”

- hard (restrictive or tight) core, soft (open or free) sleeve — outwardly obedient, but internally resistant behavior

She distinguished another pattern, which she defined as the desirable, mature pattern

- open core, free sleeve

That pattern corresponds to a kind of rest, rather than activity.

I distinguish yet another pattern:

- freely responsive core and cooperative sleeve

This pattern is neither defined by a rest condition nor by an active condition, but by free modulation between both states, characterized by freedom from entrapment in either state. In other words, there’s relatively smooth continuity between an “open core, free sleeve” condition and a freely responsive core empowered by a cooperative sleeve.

Paradoxically, it’s impossible to tell by a moment’s observation whether a person is entrapped, since their state of core and sleeve may be a momentary response (or even a frequent one). Only over the long term can we tell whether an action pattern is free or compulsorily maintained by habit. We can’t even tell, about ourselves, unless we are aware of our own Controlling Moments and the continuity of those moments with the movement into full rest.

Again, paradoxically, spontaneity shows up when the person moves easily from state to state. A true “Controlling Moment” arises from the ‘open core, free sleeve” (undefined) condition — Source.

Again, habitual fixation in a pattern at the Controlling Moment or in Powering Up interferes with this free condition, since a person can neither move freely from action to rest, nor does their action, when carried out, reflect their direction, as determined at their Controlling Moments.

Ultimately, an approach from the outside, in (such as passive bodywork) can lead only to immature patterns of function, since we activate our core from the inside, out (intrinsically), and outside-in approaches, even those that contact the intrinsic muscular or depth, are inherently extrinsic (at least at the beginning). Hence, the absolute necessity, with all kinds of bodywork, Rolfing included, for training in self-mastery to complement the changes of an outside-in approach. That training may start as movement education using the World Continuing Education Alliance, but should mature toward Transcendental Realization and stages of personal (and cultural) evolution. (See Ken Wilber’s AQAL — “All Quadrant, All Level, All Line” Kosmological (yes, spelled correctly) model. “Kosmos” means, “all that is, subjective and objective, whereas “cosmos” refers only to “astronomical reality”. “Kosmos” is to “cosmos” as “soma” is to “body”, objectively seen.)

A final quote from Ida Rolf:

Comprehensive recognition of human structure includes not only the physical body, but also the psychological personality — behavior, attitudes, capacities.

That description places The Rolf Method of Structural Integration squarely in the field of somatic education, even though its primary method harkens back to an earlier approach to human development.

MORE READING

An Advance of Somatic Education Technique — The Diamond Penetration Pandiculation Technique

The Integration Process

The Incarnation Taboo

Psychotherapy and Integral Somatic Education

The Big Pandiculation

[social_essentials]

Back Spasms — The Inside Story | Stress Muscularly Expressed

Back spasms catch us “unawares”,

so to speak.

But here’s the odd thing: when a back spasm happens, it’s most often been coming for a long time.

The Back Story of Most Back Pain

Back during a period of prolonged high stress — maybe during an employment crisis or facing deadline after deadline after deadline — you got yourself used to driving yourself hard or used to being in a state of urgency. Maybe you listen to too much news or talk radio and get “wound up”. Maybe you stayed too long in a situation you really wanted to get out of, or maybe you put and kept yourself in uncomfortable positions, by sense of necessity, that you would rather have gotten out of, and got part-way used to that, while keeping going. Or maybe you just “trained” badly or trained on top of old injuries. You’re musclebound, whatever the story, and ended up having a back spasm.

It’s been coming for a long time, your back spasm — you’ve been getting closer to the edge of cramp or spasm for a long time. You got so used to being tense and stiff that, one day, you pulled on that tenseness and stiffness and it pulled you right back, something like an internally generated whiplash action.

What If It Was a Whiplash Incident?

Maybe you were involved in an accident that yanked or jerked or jolted you a bit too much.

Then, you tightened up suddenly, experienced a sudden yank-back, and you knew you were caught. What started as a protective stiffening became a back spasm.

Back Spasms Come from and Are Maintained by Muscle/Movement Memory

“Caught in your own conditioning”– thinking about that — your back spasms come from your conditioning — how you remember your back muscles’ “normal” (habituated) condition.

We all caught in our conditioning, our memories of how things are, to varying degrees and in different ways. Had you noticed?

However, sometimes, it’s just too much, and with just one more challenge we suddenly go hard-line, uptight, tense, caught in the grip of our own conditioning, in spasm, body and mind (two aspects of the same thing). Think about it: didn’t your back spasm stop you in your tracks? mid-step? It wasn’t just “a back spasm“; it was a “you spasm“.

The Problem with a “You Spasm”

Not enough capacity, not enough tolerance for additional demand. On edge, trying to be nice, perhaps. Not much more capacity for stress, however. Used up, or close to it, in the grip.

The solution?

Recover much of that reserve capacity by dispeling obsolete tension patterns. Lose the excess tension. Get back to normal. Recover your reserve capacity. Feel like a human being. You may have forgotten what that feels like and you may not have known that you can do it, yourself.

Common Back Spasms are Simple

“Simple When You Know How”

Common Back Pain is a fairly simple condition to master. It’s just a primitive “go” reaction (“Landau Reaction“) turned on too hard and too long. You’re overheated; you’re idling too high. You can learn to turn this reflex (Landau Reaction) down and up again, temper it, recover a bunch of reserve capacity, flexibility and freedom of movement. No more spasm, no more back pain, more reserve capacity, more movability.

Back Spasms from Injury are More Complex, Take More Doing to Clear Up

Back pain from injury may consist of a number of overlying contraction patterns. However, bending over or twisting and getting a spasm isn’t an injury; it’s a malfunction that falls under “Common Back Pain”. Recovering from a complicated injury isn’t more difficult, particularly; it just takes more steps, some sorting out, and more doing, of course.

The same principle applies, either way.

Recover voluntary (deliberate) control of the muscular grip and let it relax, then deliberately use it freely and so reclaim it. Strength, reserve capacity, free control. Security.

One Right Reason

That’s one very good purpose of somatic education — to get people out of pain. It’s effective, it’s faster than more well-known or popularized methods, and it brings durable benefits under all life conditions.

Different — and More Like Yourself

A larger effect of somatic education is to train people to free themselves from the excessive grip of their conditioning; to re-acquaint people with what it feels like to feel fine; so people feel different and more like themselves.

Relief comes primarily from what the person does, secondarily from what someone else did with the person. If you do sessions of this process, you contribute at least 50% to the change, moving between effort and non-effort (in clinical sessions), or more like 90% if you’re working at a distance from me (Lawrence Gold) following recorded instructional material and taking distance-coaching, as needed.

Because the person is contributing energy, intention, and intelligence to the process, and because they’re changing from within (if guided from out), the change is theirs — theirs to maintain or theirs to re-create, if necessary. More than that, it’s faster than by externally operating methods, whether scalpel, laser, or stretching device (“spinal decompression”), longer-lasting than manipulations or interventions of many kinds. It’s longer-lasting because it covers more of the bases and from the internal control center, the self, oneself, and faster because it works from the inside, out.

MORE ON BACK SPASMS, DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES

-

How You Can Relieve Your Own Back Pain

-

On Chronic Back Pain

-

De-Spookifying Medical Terms about Back Pain

TMJ Syndrome-TMD-Bruxism Treatments

This entry is for you if you have bruxism, orofacial pain, earaches, TMJ headaches, or clench your teeth at night.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Once again, I am drawn to address common practices used to alleviate common health conditions. In this case, it’s TMJ Dysfunction (or “TMD” or “TMJ Syndrome”), a condition that people commonly expect to take months or years to clear up, but which can be cleared up in weeks by oneself or faster with clinical somatic education sessions.

The Essence of TMJ Dysfunction

Common dental practices overlook the root of the condition: neuromuscular conditioning caused by trauma (injury, previous dental work) or long-term emotional stress (particularly, anger). Even “neuromuscular dentistry” approaches the situation indirectly, by changing such things as a person’s bite pattern; the “neuromuscular” part exists in their minds, but not in their way of approaching the situation.

“Neuromuscular conditioning” means the way the brain has learned to control (or regulate) a certain function — in this case, the tension and movements of the jaws. It’s a function of what is colloquially called, “muscle memory or movement memory.

An article posted here gives the details.

Here are topics that give reasoning and details.

- Common Causes of TMD/TMJ Syndrome/Bruxism

- Symptoms of TMJ Syndrome/TMD

- Treatment for TMJ

- A New TMJ Therapeutic Approach

The common therapeutic means for addressing the condition address symptoms, rather than causes.

As a clinical somatic education practitioner, I’ve developed an effective and reliable self-relief program, which addresses exactly the underlying cause of TMJ Syndrome: the reflexive muscular action in the muscles of biting a chewing that causes the complex array of symptoms associated with TMJ Syndrome.

INTRODUCTION TO THIS TMJ SELF-TREATMENT PROGRAM

TMJ Dysfunction (TMD) Corrected

with Hanna Somatic Education

MORE:

Common Causes of TMJ Syndrome, Nocturnal Bruxism

TMJ Syndrome (also known as “TMD” and “TMJD”) includes diverse symptoms caused by reflexive actions of the muscles of biting and chewing. It comes from brain-muscle conditioning (“muscle/movement memory”) caused by trauma and/or stress. The term, “TMJ”, refers to the Temporo-Mandibular Joints — the jaw joints.

As with all conditioning, proper training techniques can alter the conditioning that controls the muscles of biting and chewing. An accelerated training process, clinical somatic education), dramatically reduces the time needed to correct TMD/TMJ Dysfunction by retraining the muscle/movement memory that controls biting and chewing.

Dentists commonly categorize TMD/TMJ Dysfunction into different types: joint arthritis at the temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ), muscular soreness (myalgia), articular disc displacement, and bite deviation.

All of these conditions reduce down to the same cause: muscle/movement memory that keeps the muscles of biting and chewing tight. The same approach can resolve them all (except for “disc displacement without reduction”, which is a surgical situation).

Let’s see how.

Degenerative Arthritis

Degenerative arthritis of the TMJ does not just “happen by itself”, nor does it result from outside influences, like an infection.

It results from excessive compression forces upon the TMJ, imposed by chronically tight muscles of biting and chewing. The joint breaks down under pressure.

Treatment must therefore retrain those muscles to a normal, low tension state, to be effective.

Muscular Soreness (Pain)

Chronically tight muscles develop muscle fatigue — the common “burn” that people go for in athletic training. People with TMJ Dysfunction experience pain in the ear or on one side of the jaw, from this condition.

Symptoms disappear nearly instantly, once muscles relax. For a lasting reduction of muscle tension and burn, a training process is needed. Faster and slower training processes exist.

Articular Disc Displacement

The articular disc of the TMJ is a pad that rides between the lower jaw (mandible) and the underside of the cheek bone (zygomatic bone), which goes from below the eyes, in front, to just before the ears on both sides. The TMJ, itself, is located just in front of the ears, and although the TMJ is the “home” position for the lower jaw, the TMJ is a very free joint. The cheek bone acts as a kind of rail along which the lower jaw rides forward and back during jaw movements, out of and back into the temporo-mandibular joint. The articular disc pads the contact between the lower and upper contact surfaces, connected to the lower jaw by a ligament with some elasticity.

When jaw muscles are chronically tight, the articular disc gets squeezed between the two surfaces, upper and lower, and may get dragged out of place by jaw movements (displacement) — a very painful condition.

If the displaced position of the disc is within the rebound capacity of the attaching ligament, the disc can return to its home position (“disc displacement with reduction”), once excessive compression forces ease. If the ligament gets stretched past its rebound capacity, the disc stays out of place (“disc displacement without reduction”).

Bite Deviations

Bite deviations do not, in themselves, cause of TMJ Dysfunction, but they are a manifestation of it. However, when combined with excessive tension in the muscles of biting and chewing, the sensation of bite deviations get magnified, experienced as the sensation of “misfit”; grinding motions (bruxism) are actually a seeking for the comfort of a fit in a rest position, which is unavailable due to the feeling of upper and lower jaw misfit that bite deviations create.

While something radical like surgery may seem to be a necessary option, it is usually sufficient (and necessary) is to bring the jaw muscles to rest. To do so increases the tolerance (i.e., comfort) of the mismatched situation to the point where it is not disturbing.

The means to do this involves retraining muscle/movement memory of the muscles of biting and chewing.

Trauma

The underlying condition for the others, trauma (a blow to the lower jaw or dental work) triggers the muscles of biting to tighten (“trauma reflex”).

Gum chewing is not a cause, in itself, of TMJ Dysfunction.

I say more about trauma, below.

Conditioning Influences

The jaw muscles, like all the the muscles of the body, are subject to control by conditioned postural reflexes (muscle/movement memory), which affect chewing and biting movements. The reason people don’t go around slack-jawed and drooling, for example, is that a conditioned postural reflex causes the muscles of biting and chewing always to remain slightly tensed, keeping jaws closed. People’s jaw muscles are always more or less tense, even when they are asleep — but the norm is very mildly tense — just enough to keep the mouth closed and lips together.

The degree of tension people hold is a matter of conditioning.

For brevity, I’ll discuss only conditions that lead to TMJ/bruxism and not the normal development of muscle tone in the muscles of biting and chewing.

These influences fall into two categories:

- Emotional Stress

- Physical Trauma

I don’t know of empirical studies that prove which of these two causes is the more prevalent, but from my clinical experience, I would say that physical trauma (and tooth and jaw pain — which induces people to change their biting and chewing actions, and which becomes habitual) is the more common causes of TMJ Syndrome, and also dental surgery, itself. (Consider the jaw soreness that commonly follows dental fillings, crowns, root canals, etc. — soreness that may last for days.)

Emotional Stress

Ever heard the expressions, “Bite your tongue”? “Grit Your Teeth”? “Bite the Bullet”? “Hold your tongue”? “Bite the Big One”? They all have something in common, don’t they? What is that? To someone who regularly represses emotion or the urge to say something, these expressions have literal meaning.

Such repression, over time, manifests as tension held in the muscles of speech — in the jaws, mouth, neck, face, and back — the same as the muscles of biting and chewing.

Physical Trauma

Although people experience trauma to the jaws through falls, blows, and motor vehicle accidents, the most common form of physical trauma (other than dental disease) is dentistry, itself, and it’s unavoidable. Dental surgery is traumatic. The relevant term is “iatrogenic” — which means “caused as a side-effect of treatment”. Every dental procedure (and every surgical procedure) should be followed by a process for dispeling the reflexive guarding triggered by the procedure. (See the video.)

No doubt, this assertion will cause much distress among dentists, and I regret that, but how can we escape that conclusion?

Consider the experience of dentistry, both during and after dental surgery (fillings, root canal work, implants, cosmetic dentistry, crown installation, injections of anaesthetic, even routine cleanings and examinations). Consider the response we have to that pain or even the expectation of pain: we cringe.

We may think such cringing to be momentary, but consider the intensity of dental surgery; it leaves intense memory impressions on the nervous system evident as patterns of tension. (Who’s relaxed going to the dentist? — or coming out of the dentist’s office?) The physical after-effects show up as tension in the jaws and neck, and often in the spinal musculature, as well — and as a host of other symptoms.

Let’s go back to our fond memories of dentistry.

If you’ve observed your physical reactions in the dentist’s surgery station, you may have noticed that during probing of a tooth for decay (with that sharp, hooked probe they use), you tighten not just your jaw (can you feel it?) and your neck muscles, but also the muscles of breathing, your hands, and even your legs. It’s an effort to remain lying down in the surgery station when, bodily, you want to get up and get away from those instruments and the dentist or hygienist wielding them.

With procedures such as fillings, root canal surgery, implants and crown installations, the muscular responses are more specific and more intense. It’s important to ask your dentist about the best way to whiten teeth has never been more popular, even amongst the 50+. For teeth near the back of the jaws, we tense the muscles nearer the back of our neck; for teeth near the front of the jaws, we tense the muscles closer the front of the throat, floor of the mouth and tongue.

This reflexive response has a name: Trauma Reflex.

Trauma Reflex is the universal, involuntary response to pain and to expectation of pain.

It centers at the location of the pain at the time of trauma and is linked to our position at the time of pain. Muscular tensions form as an action of withdrawing, avoiding, or escaping the source of pain: tensions of the jaw muscles, neck, and shoulders, with muscular involvement all the way into the legs.

In dentistry, with the head commonly turned to one side, in addition to the simple trauma reflex associated with pain, we have the involvement of our sense of position, and not just the muscles of the jaws are involved, but also those of the neck, shoulders, spine.

All of these conditions combine into an experience that goes into memory with such intensity that it modifies or entirely displaces our sense of normal movement and position. We forget free movement and instead become habituated or adapted to the memory of the trauma (whether of dental work or of some other trauma involving teeth or jaws). Our neuro-muscular system acts as if the trauma is still happening, even though, to our conscious minds, it is long past, and the way it acts as if the trauma is still happening is by tightening the muscles that close the jaws.

Since accidents and surgeries address teeth at one side of the jaws or the other, the tensions occur on one side of the jaws or the other. Thus, the symptoms of such tension — jaw pain, bite deviations, and earaches — tend to be one-sided or to exist on one side more than on the other.

The proof of the role of trauma reflex? — the permanent changes of bite and tension of the muscles of biting that have behind them a history of dental trauma — and the changes you see in the video that occur as this man is relieved of those conditioned postural reflexes.

AN OFFERING: See how”The Whole-body Yawn” reconditions the muscles of biting and chewing to normal levels — ending all symptoms of TMJ Syndrome / TMD. CLICK HERE

RELATED ARTICLE: Symptoms of TMJ Syndrome

DIRECTORY OF ARTICLES: click here.

How to Free Tight Hamstrings

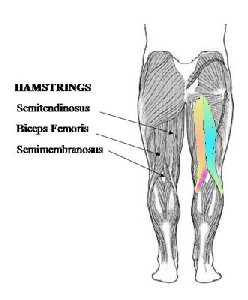

This entry discusses healthy hamstring movement, exercises to free tight hamstrings, and some of the consequences of tight hamstrings. Resources to a hamstring stretch substitute that produces superior results by retraining muscle/movement memory and to programs to improve agility appear at the end.

To free tight hamstrings, it’s important to understand their four movement functions and then to get free control of those movement functions.

- leg extension at the hip joint

- leg flexion at the knee

- rotation of the lower leg at the knee joint

- stabilization of the pelvis when bending forward

We must free them (gain control of tension and relaxation) in all four movement functions.

If we do not gain (or improve) control in all four movement functions, one or more of those movement habits will dominate control of the other movement(s).

In addition, the hamstrings of one leg work alternately with those of the other — as in walking; when the hamstrings of one leg are bending or stabilizing the knee, the hamstrings of the other leg are extending or stabilizing the other leg at the hip. In those movements, the hamstrings coordinate with the hip flexors  and psoas muscles. (Co-contraction of hamstrings and hip flexors/psoas muscles leads to hip joint and ilio-sacral (SI) joint compression.) So our approach (being movement-based) must take those relationships into account. Otherwise, we never develop the feeling of free hamstrings in their familiar movements and return habitually to their tight state which, because it feels familiar, feels “normal”.

and psoas muscles. (Co-contraction of hamstrings and hip flexors/psoas muscles leads to hip joint and ilio-sacral (SI) joint compression.) So our approach (being movement-based) must take those relationships into account. Otherwise, we never develop the feeling of free hamstrings in their familiar movements and return habitually to their tight state which, because it feels familiar, feels “normal”.

The Four Movements of Hamstrings

LEG EXTENSION AT THE HIP JOINT

That’s the “leg backward” movement of walking. The hamstrings are aided by the gluteal (butt) muscles, but only in a stabilizing capacity. The major work is done by the hamstrings. In this movement, the hamstrings, inner and outer, work together in tandem.

LEG FLEXION AT THE KNEE JOINT

That’s the “getting ready to kick” movement and also the “pawing the ground” movement. In these movements, the hamstrings, inner and outer, also work together in tandem (same movement).

To the anatomist and kinesiologist, it may seem incomprehensible (“paradoxical”) that the hamstrings are involved in both movements — leg forward and leg backward — but that’s how it is. Though the hamstrings are involved in both cases, different movements cause a different feel.

LOWER LEG ROTATION AT THE KNEE

That’s the turning movement used in skating and in turning a corner. In this movement, the inner hamstrings (semi-membranosis and semi-tendinosis) relax and lengthen as the outer hamstring (biceps femoris) tighten to turn toes-out and the inner hamstrings tighten to turn toes-in as the outer hamstring relaxes and lengthens.

STABILIZATION OF THE PELVIS WHEN BENDING FORWARD

The hamstrings anchor the pelvis at the sitbones (ischial tuberosities) deep to the ‘smile’ creases beneath the buttocks (not the crack), so one can bend forward in a controlled way, instead of flopping forward at the hips like a marionette. In this movement, the hamstrings coordinate with the front belly muscles (rectus abdominis).

In most people, either the rectus abdominis or hamstrings dominates the other in a chronic state of excessive tension, so freeing and coordinating the hamstrings involves coordinating and matching the efforts of the two muscle groups. When the hamstrings dominate, we see swayback; when the rectus muscles dominate, we see flat ribs.

Training Control of Tight Hamstrings

When training control of tight hamstrings (to free them), it’s convenient to start with the less complicated movement, first. That’s the anchoring movement that stabilizes bowing in a standing position. To see an exercise that cultivates hamstring control this way, click here.

After we cultivate control of “in tandem” hamstring movements (movement in which the hamstrings are doing the same action — lengthening, shortening or turning the lower leg), we cultivate control of “alternating” hamstring movements. To see an exercise that cultivates hamstring control this way, click here. (That link opens an email window to request a preview of The Magic of Somatics, an instructional book of somatic exercises. The preview contains the somatic exercise we are discussing.)

By cultivating control of “in tandem” and “alternating” movements, we fulfill the requirements of functions (1.), (2.), and (4.). The exercise linked in the paragraph above indirectly addresses function (3.) (lower leg rotation at the knee).

Merely to develop this kind of control is sufficient to free tight hamstrings. It’s lack of free control of the movements I have described, in which automatic postural reflexes cause tight hamstrings, that lead to many common knee injuries (including meniscal tears and chondromalacia patelli) and common hamstring pulls or tears experienced even by athletes who stretch.

One more thing: tight hamstrings go with tight back muscles. They’re reflexively connected. So if you have tight back muscles, back pain, or even back spasms, you may need to address both your hamstrings and your back muscles. As a runner, you’ll find that to do so improves your stamina, breathing, and time.

Two programs that provide those benefits appear below. Free previews are available and you’re invited to take advantage of them.

Programs That Have Somatic Exercises that Free Tight Hamstrings

Other exercises that have this effect exist in the somatic exercise programs, “Disproving the Myth of Aging” and “Free Your Psoas”, for which previews exist through the links, above.

MORE:

How Tight Hamstrings

Cause Knee Damage

and a better way to free them

Changing Muscle Memory — Manual Manipulation vs. Neuromuscular Training/Somatic Education

A basic understanding of muscle tone recognizes that the seat of control of muscles and movement is not muscles, but the brain, not “muscle memory” but “movement memory”, not “posture” but habitual or learned movement patterns (of which posture is an expression, a moment of held movement).

Lasting changes in muscle tone require movement training at the neurological (i.e., brain) level, something that manual manipulation of muscles accomplishes, at best, slowly, but which can be achieve quickly by somatic education, a discipline that rapidly alters habitual posture, movement, and muscle tone through an internal learning process that involves the brain function of memory, find more at Nixest.

More at http://somatics.com/movement.

See also, Clinical Somatic Education — A New Discipline in the Field of Health Care, by Thomas Hanna, Ph.D. — describing the dynamics of muscle memory and its dysfunction, sensory-motor amnesia (“S-MA”)

in reference to: What is Neuromuscular Therapy? (view on Google Sidewiki)