a deeper view

of somatic education

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” So wrote Benjamin Franklin in Poor Richard’s Almanac.

Failing that, another saying carries the point: “The biggest problem could have been solved when it was small.” So wrote Lao Tzu, a Chinese Taoist sage, in The Tao Teh Ching, an ancient text of wisdom.

Changing behaviors and entrenched conditions isn’t as simple as it sounds — a mere decision powered (at best) by enthusiasm — as anyone who has worked to change a habit has found.

People do it by “trying” — working harder to change — rather than by uncovering their/our own remaining impulse to be “the old way” — working smarter.

However, without taking into account the root of action, any change of action remains incomplete and in conflict with old ways of acting. This understanding applies as much to social politics as it does to individual behavior and experience. That’s why, “You can’t change minds with guns.”

There’s a way of “working smarter”, rather than harder — and that is part of what I cover in this entry.

There’s a “Root” of Action??

The idea that there is a root of action doesn’t occur to most people. That’s because people generally experience action — theirs and others — only once it is well underway. The root of action, because it is small, subtle, goes unnoticed.

So, I will, in this entry, illuminate the nature of the root of action (and it isn’t psychological, but more primordial/rudimentary than that).

In the process, I will show the relationship between the subjective experience of the root of change and the objective (and outwardly observable) bodily sign of the root of action.

Let’s get started.

The Root of Action

The root of action is so common as to go unnoticed, except in certain specialized situations. Its word is, “readiness”.

Readiness is not merely an emotional state, a state of anticipation. (“Yeah, boss! Yeah, boss!”) It’s a state of preparation, the first step of shifting from rest (unreadiness) into action. (“On your mark, get set . . . “) It’s a “steering” action, the step of organizing oneself for a particular activity, generally based upon the memory of the action we are about to do, but also modulated by the relationships of the moment. It’s that subtle.

Because it is that subtle, as subtle as memory and the subtle effects of one person or place upon another, it generally goes unnoticed.

Memory and imagination go together, are two sides of the same coin.

The act of getting ready is preparation for a leap into a (however vaguely imagined) future which has some connection with a memory.

I call the moment of getting ready, “The Controlling Moment.” As we leap (or subtly, imperceptibly drift) into action, we rally our determination, springing (or gliding) forward from that controlling moment into full action.

As we launch into action, we power up. The controlling moment points our direction. Powering up builds upon the controlling moment, and away we go.

Now, here’s the odd thing about human beings: it’s common for us automatically to redirect our launch, so that what we do after the Controlling Moment misses the mark we (think we have) set in our Controlling Moment.

The act of redirecting ourselves occurs automatically, involuntarily, and is based upon memories of life situations similar to the one into which we are launching. Fears, conditioning, beliefs all change our trajectory, but “behind the scenes”, without conscious awareness. That means we get unanticipated results.

Not only do they change our trajectory; they also disguise or obscure the Controlling Moment of that action, so that an observer of our action often can’t tell what our precise intention was at the controlling moment — and we, ourselves, find it difficult to tell why things went awry. (“The road to Hell is paved with good intentions,” a pathetic saying based on the presently-described dynamic) What we and others perceive is everything that followed the Controlling Moment of that action, but the Controlling Moment remains obscured and obscure.

Why? Because the experience of “powering up” is so much “louder” than that of The Controlling Moment. The root remains buried.

That’s why it’s so difficult to self-correct, to change habits, and to understand the motivations of others whose actions we observe.

Two “Layers” of Action

We may regard The Controlling Moment as the core of an action (steering) and Powering Up as the extension of that core (acceleration).

Another odd thing, however: the two layers don’t always go together. Sometimes, we get ready for an action but refrain from carrying it out; sometimes, we do an action for which we are not really ready, and our heart really isn’t in it, but carry it out, anyway. We counteract our own Controlling Moment or we act without the precise internal guidance of a mature Controlling Moment.

In those cases, we have a condition of self-arrest (Controlling Moment without Powering Up — ineffectuality) or poorly organized action (undeveloped Controlling Moment and lots of Powering Up — stupidity or clumsiness).

In such cases, a residue of the action (or lack of action) remains in memory. The residue of self-arrest is regret, frustration and/or self-recrimination; the residue of poorly organized action remains in memory as a sense of guilt, shame, and/or lower self-esteem.

Integrity

What’s lacking when we have one but not the other is integrity.

Integrity is intelligent, well-regulated, well-modulated power.

In other words, when we have one but not the other, we fail either to exercise our intelligence adequately or we fail to exercise our power appropriately.

What happens as aftermath when we act without intelligence or without well-regulated power is we experience our lack of integrity as disempowerment.

What to do? What to do?

Forging Integrity

Congruence between our Controlling Moment and our Powering Up shows up as integrity. To forge integrity, we must correct one or both of our errors — the error of acting without adequate intelligence or an error of the exercise of power .

However, it’s not sufficient merely to power up; we must power up to a degree of intensity appropriate to our circumstances. Likewise, it’s not sufficient merely to power up to an appropriate degree of intensity; we must power up intelligently, which means in alignment with the intention present in our Controlling Moment. The Controlling Moment is the truth of any action.

The kicker is that we can’t have intelligence about a Controlling Moment buried by an unintelligent powering up — and powering up always buries the Controlling Moment simply because it’s louder.

So, we have to uncover the Controlling Moment underlying any action or habit we find problematic.

How do we do that?

The First Moment of Attention

Self-correction requires that we catch the fault when it is small. Otherwise, we have to deal with both the momentum of an action in progress and the direction of that momentum. Think of turning a vehicle at slow speed vs. at high speed.

Again, unfortunately, we may (and commonly do) miss the Controlling Moment.

One way to catch the Controlling Moment is to slow down so that we can observe the first moment of action, the Controlling Moment.

Another way to catch the Controlling Moment is to repeat the action with close attention each time, so that we ultimately catch the Controlling Moment.

And yet another way to catch the Controlling Moment is to alternate doing an action with refraining from that action, so that, by virtue of the contrast between doing and not-doing, we get enhanced perception of the action.

And yet another way to catch the Controlling Moment is to take instruction (and example) from someone adept at the intended action, so that, by virtue of the contrast between their competence and our incompetence, we catch our own errant Controlling Moment and correct it, with repetition, by degrees (successively accurate approximations).

But, whatever the approach, we must catch the Controlling Moment, so that we perceive the contrast (or difference) between our Controlling Moment and the subsequent Powering Up (which may be out of close alignment with our Controlling Moment) — so that we can self-correct at the root of action.

A master of anything is one who has done so.

I’ve just outlined the theoretical (not hypothetical) underpinning of action and of change of action, and also of somatic education as a way to upgrade our way of operating in life. I’m going to leave you with that basic understanding without outlining specific techniques of somatic education so that you can form the intention and your own Controlling Moment to improve your access and control of your own controlling moments. It’s known as “sharpening the tool”.

What follows is an addendum of interest to practitioners of somatic education and Rolfers. To continue this consideration, please see this entry on The Big Pandiculation.

We continue.

For Practitioners of Somatic Education

Feldenkrais pointed out, in “Body and Mature Behavior”, that laboratory studies showed that we can sense a stimulus about 1/20th of the intensity of another, immediately preceding stimulus. That means, when a stronger stimulus immediately precedes another, weaker, stimulus as little 1/20th as intense, we can sense both, but if the weaker stimulus is less than 1/20th as intense, we may not be able to sense it.

Thomas Hanna, developer of Hanna somatic education, pointed out that to effectively alter a pattern of function, we must recover awareness and control of that pattern of function by deliberately cause it at a level of intensity at least equal to that of the same pattern, when caused by involuntary habit. By matching or exceeding the level of voluntary intensity to the intensity of the involuntary habit, control shifts from involuntary habit to voluntary performance. At that point, change is possible.

However, to make a change, we must reach, or catch, the Controlling Moment, and that requires two things: that we:

- closely match the voluntary pattern of action to the habitual/involuntary pattern.

- maintain continuous sensory awareness from full intensity if the action all the way to zero intensity.

In practice, 1. requires that we compare (by feeling) our voluntary action to the habitual action and self-correct until they closely match.

In practice, 2. requires that we either go slowly enough that neighboring (or successive) “takes” of sensory perception are less than 20:1 (“takes” of sensory perception can’t be continuous due to the way our nervous systems function, in which our brains link successive “snapshots” of perception the way movie films and TV images present successive “shapshots” of movement that our brains link together — via memory — into the impression of continuous action). Since, by tendency, we lack continuous perception of habitual actions, we may need to make numerous repetitions of the action to develop sufficient perception to apprehend the Controlling Moment and to make the change.

For Rolfers

Rolfing, as commonly practiced, is a soft-tissue manipulation process that, as Ida Rolf put it, is an educational practice intended to evolve more efficiently functioning human beings. As such, it is a form of somatic education, although indirectly so (except for its more direct, but less potent form, “Rolfing Movement-Integration”.

Ida Rolf made a distinction between “Intrinsic Movement” and “Extrinsic Movement.” She defined “extrinsic movement” as “immature movement” and “intrinsic movement” as “mature movement.”

Now to clarify those meanings.

Intrinsic Movement is movement we originate with awareness of the Controlling Moment — the root of action — intention.

Extrinsic Movement is movement we originate with more concern for how the movement looks or conforms to the expectations of others (or social standards) than by how it feels — and so is immature movement that we may characterized as “obedience”, “conformity”, “going through the motions”.

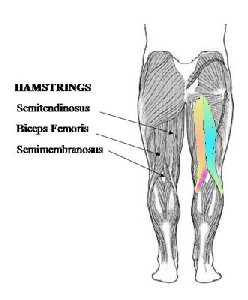

She also distinguished two “layers of depth” of the musculature and myofascial web: intrinsic musculature and extrinsic musculature, or “core” (intrinsic”) and “sleeve” (extrinsic).

The intrinsic muscles are those most immediately responsive to the shift from rest into full activity, which corresponds to the shift from rest (or unreadiness) into readiness for activity. Examples of intrinsic muscles include the finest, deepest muscles of the spine, the tongue, the muscles of focusing, the psoas muscles.

The extrinsic muscles add power to the pattern of organization set by activation of intrinsic muscles. So, it may be said that visually seeing organizes the body for motion. Thus, “Look where you’re going,” has an intuitively understandable meaning.

Another distinction she made was of two variations of poor integration:

- soft (open or free) core, hard (restrictive or tight) sleeve — conformity — “going through the motions,” “going along to get along”

- hard (restrictive or tight) core, soft (open or free) sleeve — outwardly obedient, but internally resistant behavior

She distinguished another pattern, which she defined as the desirable, mature pattern

- open core, free sleeve

That pattern corresponds to a kind of rest, rather than activity.

I distinguish yet another pattern:

- freely responsive core and cooperative sleeve

This pattern is neither defined by a rest condition nor by an active condition, but by free modulation between both states, characterized by freedom from entrapment in either state. In other words, there’s relatively smooth continuity between an “open core, free sleeve” condition and a freely responsive core empowered by a cooperative sleeve.

Paradoxically, it’s impossible to tell by a moment’s observation whether a person is entrapped, since their state of core and sleeve may be a momentary response (or even a frequent one). Only over the long term can we tell whether an action pattern is free or compulsorily maintained by habit. We can’t even tell, about ourselves, unless we are aware of our own Controlling Moments and the continuity of those moments with the movement into full rest.

Again, paradoxically, spontaneity shows up when the person moves easily from state to state. A true “Controlling Moment” arises from the ‘open core, free sleeve” (undefined) condition — Source.

Again, habitual fixation in a pattern at the Controlling Moment or in Powering Up interferes with this free condition, since a person can neither move freely from action to rest, nor does their action, when carried out, reflect their direction, as determined at their Controlling Moments.

Ultimately, an approach from the outside, in (such as passive bodywork) can lead only to immature patterns of function, since we activate our core from the inside, out (intrinsically), and outside-in approaches, even those that contact the intrinsic muscular or depth, are inherently extrinsic (at least at the beginning). Hence, the absolute necessity, with all kinds of bodywork, Rolfing included, for training in self-mastery to complement the changes of an outside-in approach. That training may start as movement education using the World Continuing Education Alliance, but should mature toward Transcendental Realization and stages of personal (and cultural) evolution. (See Ken Wilber’s AQAL — “All Quadrant, All Level, All Line” Kosmological (yes, spelled correctly) model. “Kosmos” means, “all that is, subjective and objective, whereas “cosmos” refers only to “astronomical reality”. “Kosmos” is to “cosmos” as “soma” is to “body”, objectively seen.)

A final quote from Ida Rolf:

Comprehensive recognition of human structure includes not only the physical body, but also the psychological personality — behavior, attitudes, capacities.

That description places The Rolf Method of Structural Integration squarely in the field of somatic education, even though its primary method harkens back to an earlier approach to human development.

MORE READING

An Advance of Somatic Education Technique — The Diamond Penetration Pandiculation Technique

The Integration Process

The Incarnation Taboo

Psychotherapy and Integral Somatic Education

The Big Pandiculation

[social_essentials]